Table of Contents

Healthcare providers know that not all patients are the same – some are generally healthy and need only routine check-ups, while others with complex conditions are one missed appointment away from a hospital visit. In fact, a small subset of high-risk patients can account for a disproportionate amount of healthcare utilization (for example, roughly 5% of patients drive 50% of healthcare costs). To effectively balance these extremes and improve outcomes, healthcare is embracing risk stratification. This approach involves proactively identifying which patients are at highest risk for poor outcomes or high costs, so care teams can prioritize interventions for those who need them most. In an era shifting toward value-based care – where quality and outcomes matter more than the volume of services – risk stratification has become essential for guiding precision care, reducing avoidable costs, and improving patient outcomes. Below, we delve into what risk stratification means, why it’s crucial for value-based care, various models in use, the benefits it delivers, challenges to be aware of, and what the future holds.

What is Risk Stratification?

Risk stratification in healthcare is the process of categorizing patients into risk groups based on their health status, predicted outcomes, and care needs. In practical terms, providers assess a variety of factors for each patient – from medical conditions and past utilization to social factors – and assign a risk level (for example, low, medium, or high risk). Patients in higher-risk tiers are those more likely to experience complications, hospitalization, or worsening health, and thus may require more proactive management. This systematic categorization allows clinicians and care managers to allocate resources and care intensity according to risk: high-risk patients get more attention and tailored interventions, while lower-risk patients can be managed with routine preventive care. The ultimate goal, as noted by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), is to “help patients achieve the best health and quality of life possible by preventing chronic disease, stabilizing current conditions, and preventing acceleration to higher-risk categories and higher associated costs.” In other words, effective risk stratification should lead to healthier patients who avoid complications, thereby also controlling costs.

How Risk Stratification Works:

In assessing risk, healthcare teams use both quantitative data and clinical judgment. Common inputs include a patient’s diagnoses and comorbidities, recent hospitalizations or ER visits, lab results and vital signs, medication adherence, and even psychosocial factors. Some risk stratification tools generate a composite risk score from these inputs. For example, the Johns Hopkins ACG® system groups patients into low, medium, or high-risk categories for healthcare utilization using multiple dimensions of data. Factors typically considered are:

- Clinical factors: Diagnoses, chronic conditions, and overall health status.

- Predictive cost/utilization: Prior healthcare usage and cost patterns (e.g. frequent hospital visits).

- Social determinants: Socioeconomic and environmental factors (income, housing stability, support network).

- Behavioral factors: Health behaviors and adherence (e.g. medication compliance, lifestyle risks).

By applying such factors, a risk stratification algorithm (or a care team using a scoring rubric) can flag patients who are likely to need more intensive support. The practice then uses risk status as a guide to tailor care plans – for instance, enrolling a high-risk elderly patient with heart failure into a care management program, while ensuring a low-risk young patient continues with routine wellness checks. This targeted approach helps providers anticipate patient needs and intervene early, instead of reacting after a health crisis.

Importance in Value-Based Care

Risk stratification is especially important in the context of value-based care. Value-based care (VBC) programs reward healthcare organizations for improving patient health outcomes and controlling costs, rather than paying solely per service provided. In a value-driven model, providers are accountable for metrics like hospital readmissions, chronic disease control, patient satisfaction, and total cost of care. Identifying high-risk patients up front is central to succeeding under these incentives. Here’s why risk stratification is a linchpin of value-based strategies:

- Preventive, Proactive Care: Instead of waiting for high-risk patients to land in the emergency room, care teams use risk stratification to spot them early and provide preventive interventions. This proactive approach reduces avoidable hospitalizations and adverse events, directly improving quality outcomes. As one article notes, “at the heart of value-based care lies risk stratification — classifying patients by risk and addressing potential health issues pre-emptively.”

- Optimized Resource Allocation: Healthcare resources (care coordinators, specialists, remote monitoring devices, etc.) can be directed to the patients who need them most. In value-based care, this means costly interventions are focused on high-risk individuals where they can prevent larger expenses, rather than being spread thin or used reactively. By stratifying risk, organizations ensure that intensive services (like care management or home visits) are reserved for the top-risk tier, while lower-risk patients receive cost-effective routine care.

- Improved Outcomes and Cost Control: Value-based contracts typically include financial rewards for better outcomes and penalties for poor outcomes or excess costs. Risk stratification helps improve metrics like readmission rates, chronic disease indicators, and overall population health. For example, predictive risk models embedded in VBC initiatives have enabled earlier interventions that reduced 30-day readmission rates by 12% in one study. Better outcomes naturally lead to cost savings – fewer ER visits and admissions mean lower expenditures, aligning with the value-based goal of reduced per capita cost.

- Risk Adjustment for Fair Reimbursement: In many value-based payment models (like Medicare Advantage or ACOs), providers are compensated based on the risk profile of their patients. Accurate risk stratification (often using tools such as Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) scores) ensures that organizations caring for sicker, high-risk populations receive appropriate resources and credit. This prevents a scenario where providers who take on more complex patients are financially penalized. In short, stratifying and adjusting for risk is essential to equitable, sustainable value-based reimbursement.

Overall, risk stratification provides the “compass” for value-based care. It guides care teams to deliver the right care at the right time to the right patients. By zeroing in on high-risk individuals for intensive management and keeping low-risk patients well through preventive services, healthcare organizations can achieve the triple aim of improved patient experience, better population health, and lower costs – which is exactly what value-based care strives for.

Risk Stratification Models

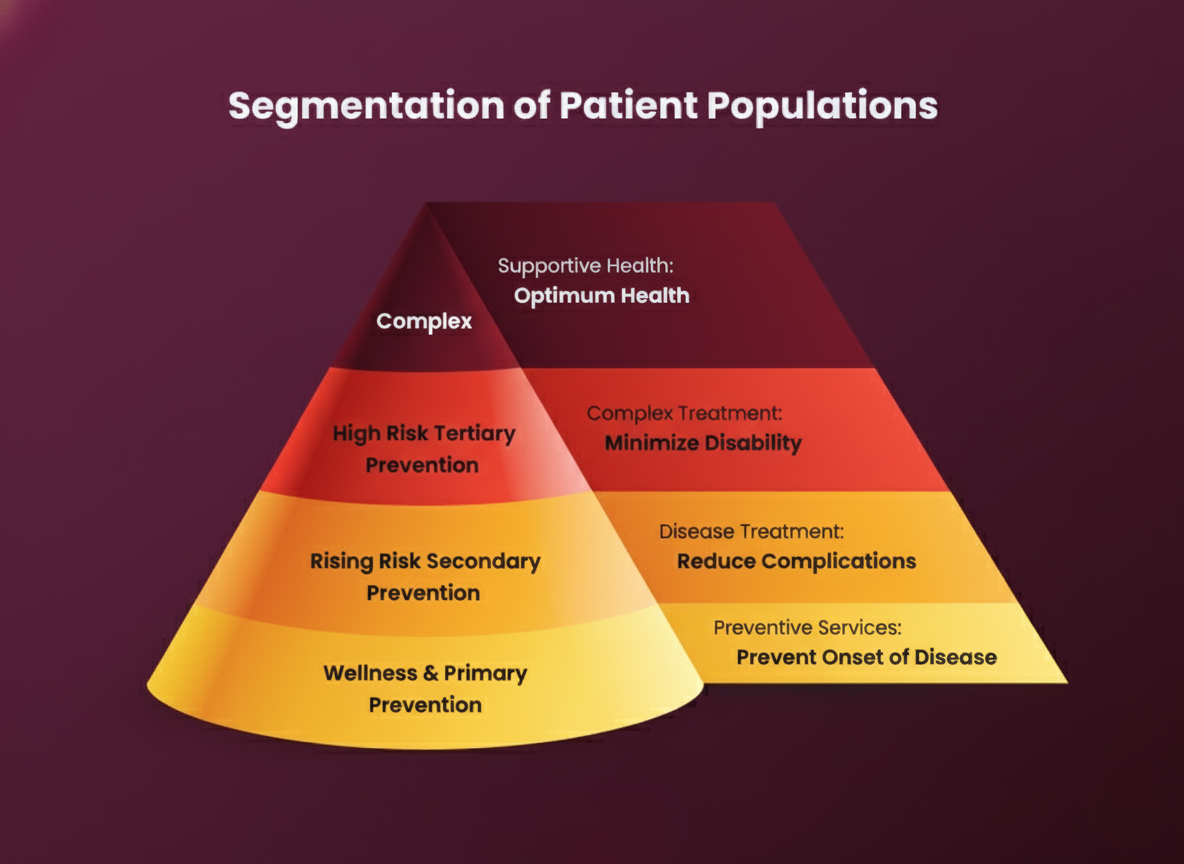

Risk stratification can be performed using different models and methodologies, ranging from simple clinical checklists to advanced AI algorithms. At its core, any risk stratification model aims to segment the patient population into tiers of risk and predict who is most likely to incur significant healthcare needs. Many organizations visualize this using a pyramid model of population risk, as shown below.

Risk stratification can be performed using different models and methodologies, ranging from simple clinical checklists to advanced AI algorithms. At its core, any risk stratification model aims to segment the patient population into tiers of risk and predict who is most likely to incur significant healthcare needs. Many organizations visualize this using a pyramid model of population risk. Risk stratification is often illustrated as a pyramid. The broad base represents the majority of patients who are low risk and mainly need preventive care (wellness and primary prevention). The middle layers represent “rising risk” patients who have emerging health issues (needing secondary prevention to reduce complications) and “high risk” patients with chronic conditions requiring active management (tertiary prevention). The small apex represents the complex, highest-risk patients who need intensive, specialized care. This pyramid model helps healthcare teams prioritize: as risk level increases, care interventions become more intensive and resources are concentrated accordingly.

Risk stratification models can be broadly categorized into a few types. Below, we discuss three common model types and their characteristics:

1. Clinical Risk Models

Clinical risk models refer to traditional risk stratification approaches that rely on medical expertise, established clinical criteria, and often simple scoring systems. These models typically use clinical data (diagnoses, age, comorbidities, etc.) and past utilization to assign a risk level. Providers have long used various scoring tools and indices to gauge patient risk, such as:

- Charlson Comorbidity Index – a score based on the number and seriousness of a patient’s chronic diseases, often used to predict mortality or complication risk.

- LACE Index – a tool that predicts a patient’s 30-day readmission risk based on Length of stay, Acuity of admission, Comorbidities, and ED visits.

- Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCC) – a risk adjustment model (used by CMS) that assigns a risk score to patients based on their diagnosed conditions and demographics, projecting future cost of care.

- APACHE II/III (ICU scoring) – used in critical care to predict mortality risk for ICU patients based on acute physiology and chronic health evaluation.

Clinical models are often rule-based or regression-based, built on medical research that links certain factors to outcomes. For example, a simple clinical model might stratify diabetics as high-risk if they have complications like heart disease and frequent hospitalizations, versus low-risk if their disease is mild and controlled. These models can be deployed via EHR templates or provider workflows relatively easily, and many EHR systems come with a built-in risk stratification module using clinical rules.

However, traditional clinical risk models have some limitations. They are usually static, updating only when a provider periodically reviews data or when new data (like a diagnosis) is entered. They may not account for real-time changes in a patient’s condition or subtler risk contributors. For instance, a Charlson Comorbidity score might not change until a new diagnosis is added, even if the patient’s health is quietly deteriorating. Moreover, these models focus mostly on medical factors and often omit social or behavioral dimensions. Despite these drawbacks, clinical risk stratification provides a foundational starting point, and many healthcare practices successfully use these models to segment patients. For example, a primary care clinic might use a condition count (number of chronic illnesses) as a simple risk stratifier: patients with 0–1 chronic conditions = low risk, 2–3 = medium risk, 4+ or any hospitalization in past year = high risk. Such approaches are intuitive and easy to implement, though they can be refined further with technology.

It’s worth noting that advanced clinical models (often available as commercial products) combine multiple data sources. Tools like the Johns Hopkins ACG® System or the Elder Risk Assessment (ERA) score use diagnoses, pharmacy data, and sometimes basic demographic risk factors to produce a more nuanced risk score. These have been validated and can outperform very simplistic methods. Still, the general trend is that healthcare organizations are moving beyond purely clinical static models toward more dynamic, data-driven approaches.

2. Predictive Analytics Models

Predictive analytics models represent the next generation of risk stratification. These models leverage large datasets, machine learning (ML), and artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to predict future health risks with greater accuracy and often in real-time. Instead of relying solely on predefined rules, predictive models learn patterns from historical data. They can incorporate a wide array of inputs—electronic health record data, claims data, lab results, medication fill data, socio-demographic data, and even patient-generated data from wearables. The goal is to identify subtle indicators that a patient may be heading towards a bad outcome (like an unplanned hospitalization) so that the care team can intervene early.

These models have shown impressive results in various studies. For example, research by Google AI scientists demonstrated that deep learning models using EHR data predicted hospital inpatient outcomes (mortality, readmission, length of stay) more accurately than traditional clinical risk scores. Similarly, machine learning algorithms have outperformed conventional tools in predicting which heart failure patients are at risk of readmission. The advantage of predictive models is their ability to handle complex, non-linear interactions among variables and to continuously improve as more data is fed into them.

Key features of predictive risk stratification models include:

- Dynamic Updating: Unlike static scores, AI-driven risk scores can update in real time. If a patient’s blood pressure has been creeping up over months, or if they suddenly miss several medication refills, a predictive model can adjust that patient’s risk level immediately. This timeliness allows providers to catch issues before they escalate. In practice, hospitals using AI-powered risk dashboards have seen tangible benefits; one report noted that using predictive analytics to flag rising-risk patients helped reduce avoidable ER visits by up to 30%.

- Multi-Modal Data Integration: Predictive models ingest a wide variety of data. They might analyze unstructured clinicians’ notes for signs of frailty, trends in vital signs, or patterns like frequent calls to an advice nurse. Importantly, many advanced models now include social and environmental data (more on that below). Incorporating diverse data types leads to enhanced accuracy. For instance, a model that knows a patient’s prescription fill gaps (medication non-adherence) and living situation (e.g. lives alone) can predict risk of complications better than a model that only sees diagnosis codes.

- Early Warning and Precision: These analytics often power risk prediction tools that highlight patients at risk for specific outcomes (like “high risk of hospitalization in next 6 months” or “high risk of opioid overdose”). By predicting who is likely to suffer an adverse event and why, predictive models enable tailored, preventive action. For example, if a model predicts a patient has a high risk of hospitalization due to heart failure decompensation, the care team can arrange a home health visit or adjust medications now, potentially avoiding the hospitalization.

Implementing predictive risk stratification requires technology infrastructure and expertise. Healthcare organizations need data scientists or analytics vendors, robust IT systems, and quality data inputs. Despite these requirements, the trend is clear: AI-driven risk stratification is transforming care delivery. As one health IT expert put it, “traditional risk models are static and don’t account for real-time changes… AI-driven analytics can adjust risk scores dynamically as new patient data comes in.” Many health systems are now integrating such tools into their population health management platforms and care management workflows, closing care gaps more efficiently. In sum, predictive analytics models take risk stratification to a more granular and proactive level, enabling truly preventive healthcare.

3. Social Determinants of Health Models

One of the most important evolutions in risk stratification is the incorporation of social determinants of health (SDOH) into risk models. Social determinants are the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes – things like economic stability, education, neighborhood and environment, food security, social support, and access to healthcare. Research suggests that these social and environmental factors can account for a huge portion of health outcomes (by some estimates, upwards of 80% of health outcome variance). Therefore, ignoring SDOH can lead to an incomplete picture of patient risk.

SDOH-enhanced risk stratification models aim to identify patients whose social needs or barriers put them at higher risk of poor outcomes, even if their clinical profile alone might not seem high-risk. For example, consider two patients with diabetes and similar clinical metrics. Patient A has a stable job, family support, and good health insurance. Patient B struggles with housing insecurity and cannot afford healthy food or medications regularly. Traditional clinical risk models might rate them equally, but common sense (and outcomes data) tell us Patient B is more likely to have complications or hospitalizations. If we integrate social risk factors into the stratification, Patient B would justifiably be flagged as higher risk, prompting additional support (like a social worker referral or community resource assistance).

Some ways SDOH are incorporated into risk stratification include:

- Adding a Social Risk Score: Tools like the PRAPARE (Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences) model create a social risk score based on factors such as poverty, housing stability, and education level. This score can be used alongside clinical risk scores. For instance, a clinic might stratify patients by clinical risk and bump them up one risk level if they have high social risk (e.g., homelessness or no family support).

- Integrated Predictive Models: Advanced AI models, such as those used by Medical Home Network (MHN) in Chicago, incorporate SDOH data directly into their algorithms. In a recent study, MHN’s AI-driven model combined claims data, demographics, and real-time inputs like social needs assessments and hospital admissions data to predict future high-cost patients. It identified more high-risk and rising-risk patients than traditional models that rely only on medical claims. The key insight was that past healthcare spending alone isn’t a complete predictor of future needs, especially in underserved populations. By including real-time social data and events (like a new housing instability or a job loss), the model provided a more actionable and equitable risk stratification, allowing care teams to devote resources to patients with the most pressing needs.

- Community-Level Risk Mapping: Some population health programs stratify by geography or community, recognizing that a patient’s ZIP code can be as predictive of health risk as their genetic code. For example, public health departments might layer maps of emergency visit hotspots with socioeconomic data to find high-risk neighborhoods. Patients in those areas could be considered higher risk due to environmental factors (lack of transportation, food deserts, pollution, etc.) and prioritized for certain interventions.

In practice, incorporating SDOH into risk stratification has demonstrated benefits. It can uncover hidden risk – patients who might look “low-risk” clinically but are actually at high risk of deteriorating due to social factors. It also aligns with broader health equity goals: by identifying social drivers of health outcomes, healthcare organizations can tailor interventions to reduce disparities. For instance, an SDOH-informed model might flag that a certain group of patients with asthma from a particular area is high-risk due to air quality issues and poor housing conditions; the intervention could then include environmental health referrals or housing assistance in addition to medical treatment.

Challenges with SDOH models: Getting accurate social data is not always easy. It often requires screening patients (e.g., questionnaires about housing, finances, etc.) or using proxy data (like area-level census information). Data privacy and patient consent are considerations, too, when using personal social information. Moreover, even once high social risk patients are identified, addressing those needs may involve resources outside the traditional healthcare system (community organizations, social services). Despite these challenges, the trend is unmistakable: social determinants are now recognized as integral to risk stratification, and healthcare providers, payers, and policymakers are increasingly investing in tools to integrate these factors. By doing so, they aim to provide more holistic, whole-person care and improve outcomes in vulnerable populations.

Benefits of Risk Stratification

Risk stratification offers a range of benefits that enhance patient care and health system performance. At its core, stratifying risk helps ensure the right patients get the right care at the right time, which leads to better outcomes and more efficient use of resources. Let’s break down the key benefits:

- Targeted Intervention: By pinpointing which patients are at highest risk (for hospitalization, complications, etc.), providers can deliver personalized interventions to those individuals. High-risk patients receive timely, intensive support (e.g. frequent follow-ups, care management programs), while lower-risk patients can be managed with routine care. This targeting means patients who need immediate attention get it promptly, preventing many health issues from escalating.

- Streamlining Resource Allocation: Risk stratification helps healthcare organizations prioritize and allocate resources optimally. For example, care coordinators and specialists can focus their efforts on a defined high-risk cohort, nurses can schedule longer appointments for complex patients, and programs like home visits or telehealth monitoring can be reserved for those likely to benefit most. This ensures finite resources (staff time, hospital beds, budget) are used where they have the greatest impact, avoiding waste and improving overall system efficiency.

- Improved Cost-Efficiency: A major benefit of focusing on high-risk patients is cost reduction. By intervening early and preventing avoidable events like emergency visits or readmissions, risk stratification helps bend the cost curve. High-risk, chronically ill patients account for a large share of healthcare spending, so preventing one hospitalization or ER visit in this group yields far larger savings than the same prevention in a low-risk group. Studies show that proactive risk management (e.g. using predictive analytics to reduce acute events) can significantly cut costs – for instance, hospitals employing risk stratified care management have seen hospitalization rates drop and total costs decrease by double-digit percentages. In practice, clinics using risk stratification report lower overall spending and improved financial performance in value-based contracts, since they avoid penalties (like readmission fines) and earn savings bonuses by managing risks.

- Enhanced Patient Engagement: When care is tailored to a patient’s risk and needs, patients often feel more seen and supported. High-risk patients might get a dedicated care manager who checks in on them, while rising-risk patients might receive education and coaching. This personalized attention can increase patient engagement in their own care – for example, a patient with uncontrolled diabetes who is identified as high-risk might receive nutrition counseling, medication reminders, and remote glucose monitoring, which motivate them to stay on track. Engaged patients are more likely to adhere to treatment plans, leading to better health outcomes. Additionally, knowing their provider is proactively monitoring their well-being (sometimes even reaching out before they themselves sense a problem) builds trust and satisfaction.

- Care Coordination and Collaboration: Risk stratification naturally leads to better care coordination. Once high-risk patients are identified, providers can assemble multidisciplinary care teams (primary care, specialists, pharmacists, social workers, etc.) and develop coordinated care plans. For example, a high-risk senior with COPD and heart failure might have her pulmonologist and cardiologist coordinating with her primary care physician and a case manager to ensure all aspects of her health are addressed. This team-based approach, guided by risk stratification, reduces duplication of services and prevents patients from “falling through the cracks.” It’s been shown that identifying patients for coordinated care programs via risk stratification improves outcomes – those patients get more consistent follow-up and support, resulting in fewer crises.

- Reducing Health Disparities: As mentioned, incorporating social determinants into risk stratification can highlight at-risk subpopulations that might otherwise be overlooked. By doing so, healthcare systems can deploy targeted programs to reduce disparities. For instance, if risk stratification reveals that patients in a certain low-income neighborhood have high risk due to poor access to transportation (leading to missed appointments and deteriorating health), a provider might introduce mobile clinics or transportation vouchers for that community. In this way, risk stratification supports health equity by ensuring high-need groups get appropriate resources. Over time, this can narrow gaps in outcomes between different socioeconomic or racial groups.

- Supports Value-Based Care Goals: All the above benefits feed into success in value-based care. Targeted interventions mean better clinical outcomes; efficient resource use means lower costs; improved engagement and coordination mean higher patient satisfaction and quality scores. Risk stratification, therefore, is a foundational capability for any organization looking to excel under value-based payment models. It provides the data-driven framework to achieve the core aims of VBC: better care, smarter spending, and healthier populations.

In summary, when done well, risk stratification creates a win-win: patients receive more appropriate, proactive care, and the healthcare system operates more effectively and cost-efficiently. To illustrate these benefits further, let’s examine a few specific areas improved by risk stratification: patient outcomes, cost reduction, and care coordination.

Patient Outcomes

Effective risk stratification has a direct, positive impact on patient health outcomes. By identifying high-risk patients and intervening early, providers can prevent complications or worsening of diseases, leading to healthier, more stable patients. A classic example is in chronic disease management: if a clinic knows which patients with hypertension or diabetes are at highest risk for, say, a stroke or hospitalization, they can intensify management for those patients (more frequent monitoring, medication adjustments, education on warning signs) and thereby prevent many adverse outcomes.

Studies and reports back this up. In primary care, timely interventions for high-risk individuals lead to better health outcomes and fewer serious events. For instance, one program that stratified and closely managed high-risk heart failure patients saw improvements in functional status and a reduction in acute exacerbations. Another example: risk stratification tools have been used to flag patients likely to skip medications or follow-ups, allowing care teams to reach out and re-engage them – this improves disease control and reduces the chance of a health crisis.

Preventive care is another domain where outcomes improve. Risk stratification can highlight “rising-risk” patients (those not very sick now but with many risk factors) who might benefit from prevention programs. By enrolling these patients in lifestyle modification classes or early specialty referrals, providers can stop the progression of disease. The AAFP notes that a key aim of risk stratification is preventing patients from accelerating to higher-risk, higher-acuity categories. Achieving this means those patients avoid things like uncontrolled diabetes leading to neuropathy or kidney failure, or mild COPD not becoming severe COPD – clearly better health outcomes for the individuals.

One concrete outcome measure often cited is hospital readmissions. Patients who are identified as high-risk for readmission can be given enhanced discharge planning and post-discharge support (like follow-up calls, home visits). As a result, readmission rates drop, which is a significant quality win. In a value-based care setting, a reduction in 30-day readmissions not only reflects better patient recovery but also avoids penalties (for Medicare patients). Similarly, mortality outcomes can improve when high-risk patients are managed proactively – e.g., sepsis early warning systems (a form of risk stratification in the hospital) have reduced in-hospital mortality by triggering rapid responses.

In short, risk stratification saves lives and improves quality of life. Patients achieve more stable control of chronic conditions, suffer fewer acute episodes, and maintain better overall health. They receive “the right care at the right time,” which is exactly what outcome-oriented healthcare strives for.

Cost Reduction

The financial benefits of risk stratification are significant. By reducing preventable healthcare utilization and focusing resources efficiently, risk stratification helps curb unnecessary spending. Consider this: High-risk patients with multiple chronic conditions drive the bulk of healthcare costs (as noted, 5% of patients can account for ~50% of costs). If we can even moderately improve care for that 5%, the cost savings are substantial. Risk stratification is the mechanism to do exactly that – identify those high-cost patients and manage them to avoid the most expensive outcomes.

One way costs are reduced is through fewer hospitalizations and emergency visits, which are among the costliest services. When a predictive model flags a patient who is headed toward an ER visit (say, due to worsening heart failure), and the care team intervenes with a medication tweak or a same-day clinic visit, a potential $5,000 ER trip and $15,000 hospital admission might be averted. Multiply such interventions across a population, and the savings add up. In fact, healthcare organizations that have systematically applied risk stratified care management have reported 15-30% reductions in hospitalization or ER utilization rates for targeted groups, translating to millions in savings.

Another aspect is preventing chronic disease complications, which are expensive to treat. For example, tight control of blood sugar in high-risk diabetics (achieved by identifying them and ensuring they get extra support) can prevent complications like amputations or dialysis down the road. Those complications are extremely costly, so prevention saves money long-term. While it’s hard to “see” the cost of an event that didn’t happen, population-level studies confirm that areas or systems with robust preventive care have lower per-capita healthcare costs over time.

Risk stratification also contributes to cost efficiency by ensuring each level of care is used appropriately. Low-risk patients, for instance, might not need specialist referrals or advanced imaging; keeping their care streamlined avoids overtreatment costs. High-risk patients, on the other hand, get intensive care which prevents even costlier outcomes. In effect, stratification prevents both overuse and underuse of healthcare resources, both of which have cost implications.

For providers in value-based contracts (ACO shared savings, capitated arrangements, etc.), these cost reductions directly improve the bottom line. If you can lower the total cost of care for your population while maintaining quality, you retain more of the capitated payments or earn shared savings bonuses. Risk stratification is a critical tool for meeting these financial targets, as it allows focusing interventions where they will yield the greatest cost avoidance.

Finally, consider operational costs: risk stratification can help practices use staff more effectively (for example, dedicating nurses to care management for the top 10% high-risk patients yields more ROI than spreading their time thin across all patients). By stratifying, a practice might decide to invest in a diabetes educator only for those at highest risk, rather than paying for everyone to have that resource. This kind of targeted allocation improves the cost-effectiveness of every dollar spent on personnel or programs.

In summary, by preventing expensive health crises and ensuring efficient care delivery, risk stratification cuts wasteful spending. It is a cornerstone of cost containment in modern healthcare. Patients benefit from fewer bills and payers/providers benefit from lower expenditures – a true win-win.

Care Coordination

Improved care coordination is another major benefit of risk stratification, closely tied to better outcomes and patient satisfaction. When high-risk patients are identified, it becomes clear that these patients often have complex needs that span multiple providers and settings. Risk stratification gives healthcare teams a clear signal on who requires active coordination and follow-up, essentially creating a priority list for care management efforts.

For high-risk patients, simply having a primary care visit now and then isn’t enough; they might see specialists, have home care needs, require social services, etc. Risk stratification programs typically assign such patients to care coordinators or case managers who act as quarterbacks for their care. This leads to more synchronized care: the primary doctor knows what the cardiologist did, the nurse care manager ensures the patient understands their medications and follows up on referrals, and so on. The result is that the patient’s care is delivered in a more organized, continuous fashion rather than a fragmented, episodic way.

Take for example a patient with COPD, diabetes, and depression – a classic high-risk profile. Through risk stratification, the care team flags this patient and creates a coordinated care plan. A case manager might arrange regular phone check-ins to monitor COPD symptoms, a pharmacist might review their medications for any conflicts, a mental health counselor might be looped in to address depression (which if unmanaged could worsen their ability to manage other conditions). All these professionals communicate and share information. This level of coordination helps avoid pitfalls like medication errors, conflicting advice, or the patient falling off the radar. It also improves the patient’s experience because they feel supported by a team that’s on the same page.

Even for moderate or rising-risk patients, coordination is beneficial. For instance, a patient at rising risk could be referred to a nutritionist and a diabetes education class—risk stratification ensures those coordination efforts happen before the patient becomes high-risk.

Risk stratification can also inform specialist referrals and transitions of care. It can highlight patients who would benefit from seeing, say, a nephrologist early because their kidney function is trending downwards, or those who need palliative care involvement. Ensuring timely referrals means the patient gets comprehensive care. It’s been noted that risk stratification is used to select patients who would benefit from working with a specialist or from coordinated care solutions. This ensures no one who truly needs advanced care is overlooked.

Additionally, when patients are stratified, healthcare teams often implement structured communication routines like daily huddles or weekly meetings focusing on high-risk patients. In these, they discuss care plans, recent hospital visits, and any barriers. This kind of team communication is a hallmark of good care coordination and arises naturally from a risk-focused approach.

From a systems perspective, improved coordination reduces redundant tests and procedures (saving cost) and prevents miscommunications that could lead to errors. For the patient, it means smoother transitions (such as from hospital to home – where a coordinator calls them within 48 hours to follow up), and overall a more seamless journey through the healthcare system.

In short, risk stratification activates a higher level of care coordination for those who need it most. It aligns multiple providers and services around the patient, which improves continuity of care and ultimately health outcomes. Patients with complex conditions especially benefit from this “air traffic control” approach that risk stratification makes possible, ensuring they don’t navigate their health challenges alone or unassisted.

Risk Stratification Challenges:

While risk stratification is powerful, implementing it is not without challenges. Healthcare organizations often encounter obstacles in data, technology, and ethics when developing and using risk models. Recognizing these challenges is important to address them effectively:

1. Data Quality and Integration

Data is the lifeblood of risk stratification, and data-related issues are perhaps the biggest challenge. To stratify patients accurately, you need comprehensive, high-quality data on each patient. This includes their medical history, current clinical measurements, utilization history, and ideally social factors. In reality, patient data is often scattered across different systems and may be incomplete or inaccurate. Many providers struggle with data integration – combining data from electronic health records (EHRs), pharmacy systems, hospital databases, and external sources into one unified view. If your risk model only sees part of the picture, it might misclassify patients. For example, if a patient was hospitalized at an outside facility that isn’t captured in your EHR, a risk algorithm might mistakenly label them low risk because it’s unaware of that hospitalization.

Data quality is another facet: EHR data can have errors (diagnosis codes not updated, missing lab results if done outside network, etc.). Social determinants data can be hard to quantify and keep current (a patient’s financial or housing situation can change quickly). Moreover, claims data used in many traditional models is lagged by several months, so it might not reflect a patient’s current status.

Interoperability standards like HL7 FHIR are helping by making it easier to pull data from multiple sources, but many organizations still face siloed systems. Smaller clinics might not have IT systems that talk to one another (e.g., mental health records separate from medical records), leading to fragmented data. Overcoming these silos often requires investment in health information exchange platforms or data warehouses – which can be costly and technically complex.

Another data challenge is ensuring real-time or up-to-date information. Risk is dynamic; a model should ideally know if a patient showed up at the ER yesterday or if their latest lab showed kidney function decline. Setting up feeds for real-time data (e.g., ADT feeds for admissions/discharges, or integrations with lab systems) is not trivial for many practices.

In summary, poor data quality or integration can lead to gaps in patient insights. A risk stratification is only as good as the data feeding it. If not addressed, this challenge can result in missed high-risk patients or misidentifying someone as high-risk when they’re not (false alarms). Health IT teams and population health managers must work continuously to improve data completeness – whether by manual data reconciliation, patient surveys (to get missing info), or technical interfaces between systems. Data governance policies also need to be in place to standardize how data is entered (so that, for example, diagnoses and social needs are coded consistently across the organization). Until data flows seamlessly and accurately, risk stratification will always have an uphill battle.

2. Technology and Implementation Limits

Even with good data, the technology and expertise required to implement advanced risk stratification can be a barrier. Not all healthcare organizations have a team of data scientists or can afford sophisticated analytics software. Smaller or resource-limited practices might rely on rudimentary methods (like manual spreadsheets or basic EHR reports) for risk stratification, which can limit the effectiveness of the process.

Adopting a commercial risk stratification tool or predictive analytics platform often involves significant cost and training. Organizations must consider factors like: Can our current IT infrastructure support this tool? Do we need to hire new analysts or consultants to use it? How will it integrate into clinical workflow? These considerations can be daunting. In fact, key factors a practice should evaluate before choosing a risk stratification model include the cost of the tool, the accessibility of required data, ease of implementation with their IT, and the relevance to their patient population. If any of these factors don’t align, the implementation may struggle or fail.

There’s also the challenge of workflow integration. Introducing a new risk score or stratification process means clinicians and staff need to change how they do things – maybe a new dashboard to check every morning, or new care management protocols for those flagged high-risk. Busy clinics might resist these changes, especially if they perceive it as extra work without immediate benefit. It takes strong change management and leadership support to embed risk stratification into routine care (for example, ensuring every morning huddle starts with reviewing high-risk patient lists, or empowering nurses to act on risk alerts).

Additionally, advanced models (like AI) can sometimes be a “black box,” and clinicians may be skeptical about trusting an algorithm’s output. Without clear understanding or explainability, providers might ignore the risk strat flags, which negates the whole point. Therefore, implementation often requires educating the care team on how the model works (at least at a high level) and why it’s useful.

Technical limitations can also crop up: a model might work well for a general adult population but not be calibrated for pediatric patients or OB/GYN patients, etc. If a practice serves a unique demographic, off-the-shelf models may need customization – which again demands tech expertise.

Computing infrastructure is another piece: real-time predictive analytics might require robust servers or cloud computing resources. Not every clinic has that readily available, though cloud-based solutions are making it easier for even smaller entities to use heavy analytics (at a price, of course).

Lastly, maintaining and updating models is a challenge. A risk model is not a “set and forget” tool; it needs periodic recalibration, especially if population characteristics change or if new data sources are added. Keeping the model up-to-date (or upgrading to newer, better models) requires ongoing work. If an organization lacks a champion or team dedicated to this, the model can quickly become stale or less accurate over time.

In summary, implementing risk stratification – especially the high-tech, AI-driven kind – requires substantial resources, planning, and change management. Organizations must navigate cost, data requirements, integration with existing systems, and user adoption. Those that can overcome these challenges reap the rewards; those that can’t may end up using only basic stratification approaches and not capturing the full value. As one healthcare executive advised, do a careful assessment of needs and capabilities, pilot test a model, and ensure leadership buy-in before rolling out a risk stratification program broadly.

3. Ethical and Privacy Concerns

Risk stratification, particularly when powered by AI and big data, raises several ethical concerns that healthcare providers and developers must be mindful of:

- Bias and Fairness: Perhaps the most prominent concern is the potential for algorithms to perpetuate or even exacerbate biases. If the data used to train a predictive model contains biases (reflecting historical inequities in healthcare access or treatment), the model may produce biased risk predictions. A notable example is a widely used commercial risk score algorithm that was found to have. This algorithm, which helped determine who gets extra care management, was using healthcare cost as a proxy for need. Because historically less money was spent on Black patients (due to unequal access, etc.), the algorithm mistakenly scored Black patients as generally “lower risk” than equally sick White patients. In practice, this meant healthier White patients were getting into care management programs ahead of Black patients who actually had more severe health issues. Such biases in risk stratification can worsen disparities if not addressed. Ensuring algorithmic fairness is a major challenge – models should be tested for bias across race, gender, socioeconomic status, and adjusted if needed so that risk scores truly reflect need, not historical utilization patterns.

- Transparency: Related to bias is the issue of transparency. Clinicians and patients may ask, “Why am I (or is this patient) rated high risk?” If the model is a complex machine learning algorithm, it might be hard to explain in simple terms. A lack of transparency can undermine trust in the system. Ethically, there’s a push for more “explainable AI” in healthcare so that the rationale behind a risk score can be communicated. For instance, instead of just labeling a patient high risk, an algorithm might highlight that the patient’s risk is driven by factors like “uncontrolled diabetes + recent hospital visit + living alone with limited support.” That kind of explanation helps providers validate and act on the risk information. When models are black boxes, providers might be hesitant to follow their guidance, or patients might be confused or fearful about being labeled without understanding why.

- Patient Autonomy and Labeling: Labeling patients as “high risk” could potentially have unintended consequences. Patients might internalize the label negatively or face discrimination. For example, could a “high risk” label influence an insurer’s decisions or a provider’s attitude in a way that isn’t beneficial? It’s an ethical concern to ensure that labels are used to help patients, not to limit their care. Also, patients should ideally be informed and involved in their care plans – if a patient is identified as high risk for non-adherence, how do we involve them in addressing that without casting blame? Respecting patient autonomy means perhaps getting consent for certain uses of their data or at least being transparent that these risk stratification processes are happening.

- Privacy and Data Security: To stratify risk, especially using SDOH and other extensive data, healthcare systems are aggregating a lot of personal information. This raises privacy concerns. Patients might be okay sharing medical info but less comfortable with healthcare systems using data about their income, neighborhood, or buying habits (some third-party data vendors provide such info). There’s an ethical obligation to protect patient data and use it responsibly. Data breaches are a risk whenever big data is collected. Moreover, some patients might not want to disclose social information out of fear of stigma. Ensuring robust privacy safeguards and being transparent about data use is crucial to maintain trust.

- Intervention Ethics: Another angle is, once you’ve identified someone as high risk, what you do with that information has ethical implications. For example, if an algorithm flags someone as high suicide risk, the care team has a responsibility to act (which is good, but also must be done sensitively to respect patient rights). Or if someone is high risk for costing a lot, a financial-minded entity might be tempted to “manage them out” (for instance, an insurer might drop a high-cost patient – which is unethical in healthcare and illegal in many cases, but one must be cautious that risk stratification isn’t misused in such a way). The focus should always remain on using risk info to provide better care, not deny it.

- Dependency and Automation Bias: Ethically, we also worry that clinicians might over-rely on algorithms (automation bias) and possibly ignore their own judgment or patient preferences. If a risk tool isn’t perfectly accurate (none are), a slavish adherence to it could be harmful. For example, if a model somehow fails to flag a patient who is actually in trouble (false negative), clinicians still need to use their eyes and ears and not become complacent. Balancing algorithm guidance with human judgment is important for ethical patient care.

Addressing these ethical concerns involves several strategies: using diverse and representative data to train models, performing bias audits on algorithms regularly, incorporating fairness adjustments (there is growing research on algorithmic fairness in healthcare), ensuring privacy by following HIPAA and perhaps de-identifying data when possible, and being transparent with both clinicians and patients about how risk scores are generated and used. Some health systems have even formed ethics boards to review AI use in patient care.

In the end, risk stratification should be a tool for good – to enhance care and equity – and not inadvertently worsen inequalities or erode trust. It’s an ongoing effort to ensure that as we adopt more advanced analytics, we also bolster our ethical guardrails.

Future Outlook

The future of risk stratification in healthcare is dynamic and highly promising, fueled by advances in technology, data science, and an increasing emphasis on holistic patient care. We can expect risk stratification to become even more precise, proactive, and seamlessly integrated into healthcare delivery in the coming years. Here are some key trends and developments shaping the future outlook:

- Advanced AI and Real-Time Risk Prediction: Artificial intelligence will continue to revolutionize risk stratification. We’re moving toward a reality where AI can forecast a person’s risk for multiple conditions with remarkable accuracy, even decades into the future. For example, emerging AI models can analyze genetic information alongside clinical data to predict the likelihood of developing certain diseases 5, 10, or 20 years down the line. This will enable truly preventive interventions. By 2025 and beyond, expect wider adoption of predictive AI tools that continuously learn from new data and update patient risk scores in real time. This means if a patient’s wearable device detects an arrhythmia tonight, tomorrow the risk platform flags them for a check-in – risk stratification will be an always-on, live process rather than a periodic review.

- Precision Medicine and Genomic Data Integration: The future will likely see risk stratification incorporating genomic and biomarker data to a greater extent. Polygenic risk scores (which aggregate the effects of many genetic variants) are already showing promise in identifying individuals at high inherited risk for conditions like heart disease or breast cancer. Integrating these into risk models could lead to a more personalized stratification – not just who is high risk today, but who is predisposed to become high risk in the future, so that early preventive steps can be taken. As genomic testing becomes more common, a patient’s genetic risk profile might be part of their health record that feeds into risk algorithms.

- IoT and Remote Monitoring: The Internet of Things (IoT) in healthcare – including smart wearables and home monitoring devices – will significantly enrich risk stratification models. Constant streams of real-time patient data (heart rate, blood glucose, oxygen levels, medication adherence via smart pill bottles, etc.) mean that risk assessment can adjust day by day. If a normally stable patient’s remote blood pressure readings start trending upward, the system will catch it and adjust their risk level accordingly, prompting earlier intervention. Remote monitoring has already been shown to reduce hospital readmissions by about 25% through early detection of issues, and those benefits will grow as more patients use these devices. Essentially, the home will become an extension of healthcare, and risk stratification will draw from both in-clinic and at-home data to create a continuous health surveillance (in a positive sense) that keeps patients safer.

- Integration of SDOH and Community Data at Scale: In the future, we will likely have much better data on social determinants – possibly through regional or national data exchanges. We might see standardized SDOH data elements (there are initiatives already to standardize how SDOH information is collected and shared). This will allow risk stratification models to use community-level data (like neighborhood air quality, local crime rates, or community health resources available) to refine individual risk scores. There is also a push toward “whole-person” care, meaning risk stratification will not just trigger medical interventions but also social interventions. For example, a high social-risk patient might be auto-referred to a community health worker program alongside medical follow-up. The lines between healthcare and social care will blur in risk management, because the industry recognizes that’s how we truly improve outcomes.

- Better User Interface and Workflow Integration: We’ll likely see risk stratification tools become more user-friendly for clinicians. Instead of separate dashboards that busy providers have to remember to check, risk insights will be embedded directly into the EHR interface and clinical workflow (e.g., an alert pops up in the chart that “this patient is high risk for hospitalization within 3 months; consider scheduling a follow-up in 2 weeks”). Natural language processing might summarize risk factors from doctor’s notes to contribute to the risk score behind the scenes. The goal will be making the technology invisible and the insights actionable – clinicians shouldn’t have to be data analysts to benefit from these tools.

- Continuous Learning Health Systems: As more healthcare systems implement these advanced stratification models, a feedback loop will emerge. Outcomes data (did the predicted event happen or not? did the intervention work?) will flow back to refine the models. We’ll have learning systems where each care interaction makes the model smarter. Also, collaboration between organizations (sharing de-identified data) could lead to more powerful, generalized models that everyone can use. It’s conceivable that national networks of data may produce risk stratification benchmarks or even AI that can predict public health trends (like identifying risk of an infectious disease outbreak in a region by aggregating data).

- Ethical AI and Fairness Controls: Given the concerns we discussed, future risk stratification will also come with built-in fairness and bias monitoring. Regulators and industry groups might establish standards for validating that risk models don’t discriminate. We may see required periodic audits or certification processes for algorithms, especially as they become more central to care decisions. This is a positive development – ensuring that as tech advances, it does so equitably.

- Greater Patient Engagement through Transparency: The future might also involve sharing risk information more openly with patients. Right now, risk stratification is mostly a “back-end” process clinicians use. But imagine if patients had access to a personalized risk dashboard through patient portals: it could increase their engagement (for example, “Your risk for heart complications is high; here are 3 things you can do and programs available to help reduce it”). As digital health literacy improves, patients might take a more active role in modifying their risk factors if they’re made aware of them in a clear way.

Looking ahead, risk stratification will be a cornerstone of preventive, personalized healthcare. It aligns perfectly with the shift from volume to value, and from reactive care to proactive care. We foresee a healthcare system where every patient’s risk profile is continuously updated and managed as part of routine care – much like vital signs are monitored today. High-risk patients will receive swift, tailored interventions; moderate-risk patients will get support to prevent escalation; low-risk individuals will be kept well with minimal intervention but never falling off the radar. This vision leads to healthier populations, less strain on hospitals, and more efficient use of resources.

In conclusion, the evolution of risk stratification signals a future where healthcare is data-driven, predictive, and patient-centric like never before. Providers, policymakers, and health tech innovators should invest in and embrace these tools now, as they will form the backbone of tomorrow’s healthcare delivery. The time to act is now: healthcare organizations that leverage modern risk stratification and care management strategies will be poised to lead in delivering high-value care, improving patient lives while wisely managing resources. By harnessing the power of data and technology ethically and effectively, we can ensure that every patient gets the care they need before a crisis happens – truly fulfilling the promise of a smarter, healthier future for all.

FAQ

Q: What is risk stratification in healthcare?

A: Risk stratification in healthcare is a systematic method of categorizing patients by their health risk levels. Providers evaluate factors like medical conditions, past hospital use, and social needs to assign each patient a risk status (for example, low, medium, or high risk). This helps identify which patients are most likely to experience serious health issues or hospitalizations in the near future.

Q: How is risk stratification used in value-based care?

A: In value-based care models, providers are rewarded for keeping patients healthy and reducing unnecessary costs. Risk stratification is a critical tool in this approach. By stratifying patients, healthcare organizations can focus their resources on high-risk individuals who are likely to drive up costs with complications or hospital visits.

Q: What are some examples of risk stratification models?

A: Examples of risk stratification models range from simple to complex. On the simpler side, many primary care practices use a condition count or tiering system – e.g., 0-1 chronic conditions = low risk, 2-3 = medium, 4+ or recent hospitalization = high risk. More formal tools include the Charlson Comorbidity Index, which assigns points for different illnesses to predict risk of death or hospitalization, and the LACE Index for readmission risk which uses Length of stay, Acuity, Comorbidities, and ER visits. Health plans and Medicare use the Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) model, which calculates a risk score based on diagnoses and demographics (useful for predicting costs).

Q: Why is risk stratification important for patient care?

A: Risk stratification is important because it makes patient care more proactive, personalized, and effective. Instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, providers use stratification to determine who needs what kind of care intensity. High-risk patients (for example, someone with multiple chronic illnesses and recent hospitalizations) can be flagged to receive interventions like frequent follow-ups, home care visits, or specialist consultations before they suffer a serious complication. This can prevent health crises and stabilize the patient’s condition. Medium-risk patients might get moderate interventions like chronic disease coaching to keep them from becoming high-risk.

Q: Can risk stratification help reduce healthcare costs?

A: Yes, risk stratification is a proven strategy for reducing healthcare costs. The principle is that a small percentage of patients (often those with complex, uncontrolled conditions) account for the majority of healthcare spending. By identifying these high-cost, high-need patients through stratification, healthcare systems can target them with intensive care management that prevents expensive events like emergency visits, hospitalizations, or complications.